Articles of Interest

Better Design of PfAD for Pension Plan Funding

Introduction

The funding of defined benefit (DB) pension plans is a complex and challenging issue that requires careful management and attention. In recent years, Canadian jurisdictions have adopted a new funding framework known as "going concern plus" to lower the amount and instability of required contributions to DB plans by eliminating or easing solvency funding requirements while strengthening the going concern funding requirements. A key component of this new funding framework is the provision for adverse deviations (PfAD), which is a funding reserve that is required to absorb the impact of any adverse experience that deviates from the assumptions made in the actuarial valuation.

In this article, we will examine how different PfAD designs would have impacted the funding position of a DB plan over a 70-year period from 1950 to 2020. We will analyze the results and provide some observations and recommendations for policymakers.

Different Jurisdictions, Different PfAD Designs

The PfAD is typically determined as a percentage of the plan's going concern liabilities and normal cost for determining its funding requirements. The PfAD design differs across Canadian jurisdictions. For example, in Québec, it is based on the proportion of plan assets allocated to variable yield investments and the ratio of the duration of the bond portfolio of the pension fund to the duration of plan liabilities. In Ontario, it is calculated based on the proportion of plan assets allocated to variable yield investments and whether the plan is open or closed. In British Columbia, it has a minimum of 5% and is generally calculated as five times the monthly long-term Government of Canada bond yield at the valuation date. Other jurisdictions, such as Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Manitoba, have PfAD designs similar to Ontario.

Ontario and Québec both have a static PfAD design based on the plan's investment policy, whereas British Columbia's PfAD is independent of the investment policy but varies based on the long bond yield at each valuation date. In our paper titled 'A Stochastic Analysis of Policies Related to Funding of Defined benefit Pension Plans'[①] (referred to as 'Ma's paper'), we argue that policymakers should adopt a PfAD that varies based on the evolving funding position and investment risk of the plan. The following section demonstrates how different PfAD designs would impact the funding position of a DB plan.

Historical Analysis of PfAD Designs

To evaluate the effects of various PfAD designs on a DB plan, we conducted a 70-year historical analysis from 1950 to 2020. The plan was fully funded at the beginning of the period and had a stationary membership profile, along with an investment policy consisting of a 50/50 target asset mix. We used the pension projection model described in Ma’s paper to project the plan's funded ratios over the period. Any deficits or surpluses, after taking into account the PfAD provision, were amortized over a 10-year period on a fresh start basis.

The following PfAD design alternatives were included in the analysis:

A. A static PfAD of 9.1%

B. A dynamic PfAD determined as follows:

i. 9.1% if the plan’s funded ratio is within the range between 0.9 and 1.1

ii. If the funded ratio is outside the range, the PfAD of 9.1% will be increased (decreased) by 2.4% for each 10% the funded ratio is lower (higher) than 1.0

iii. The minimum PfAD is 0%

C. 5 times the long Canada bond yield at the valuation date (as prescribed in British Columbia)

Note that the PfAD parameters for Designs A and B are based on the modelling results, corresponding to a 50/50 target asset mix, provided in Section 6 of Ma’s paper.

A base case with no PfAD was also included.

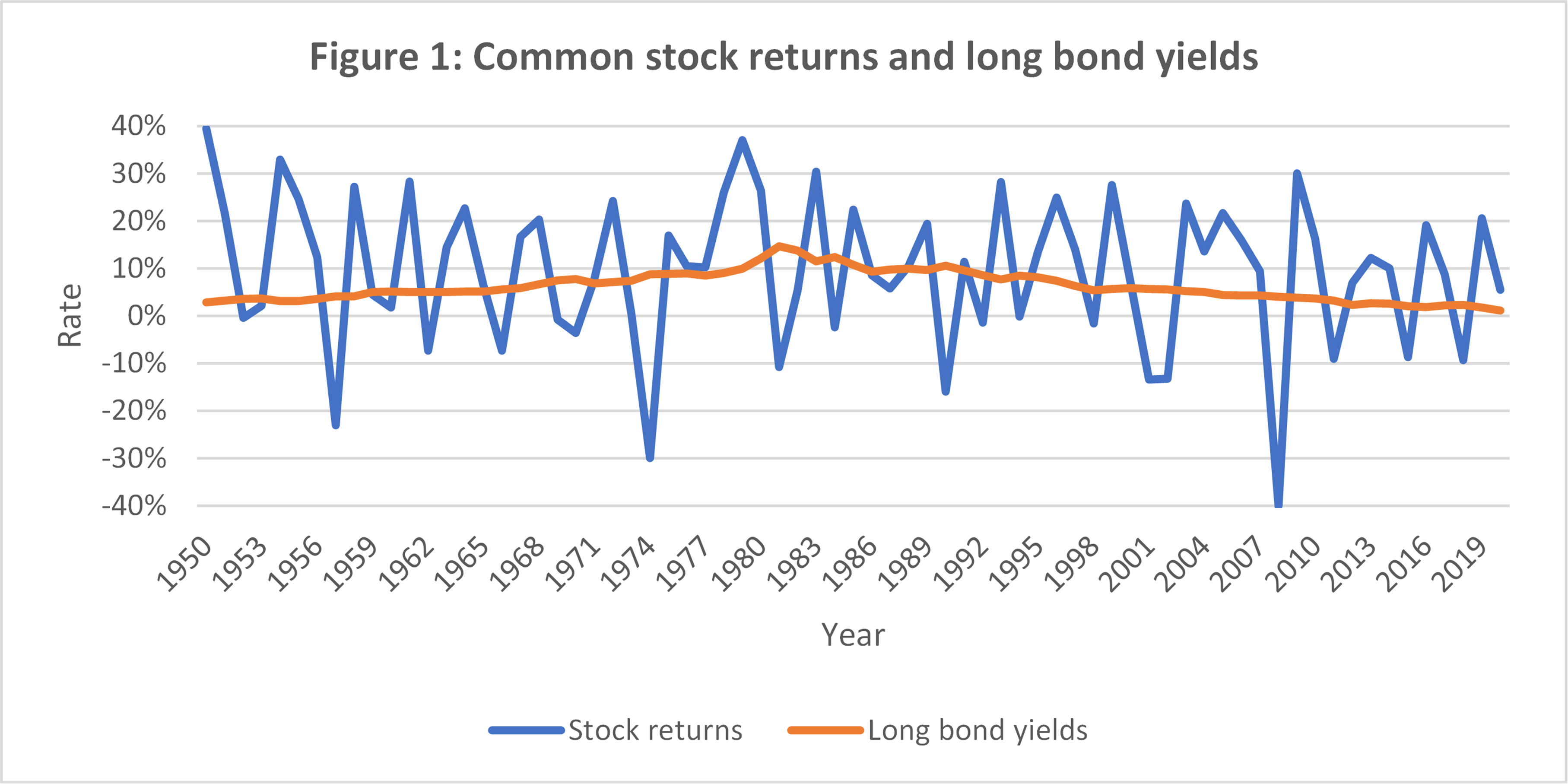

For the development of pension fund returns and bond yields, we used the historical federal bond yields and common stock returns provided in the Report on Canadian Economic Statistics 1924–2020, published by the Canadian Institute of Actuaries[②]. The relevant data are plotted on Figure 1.

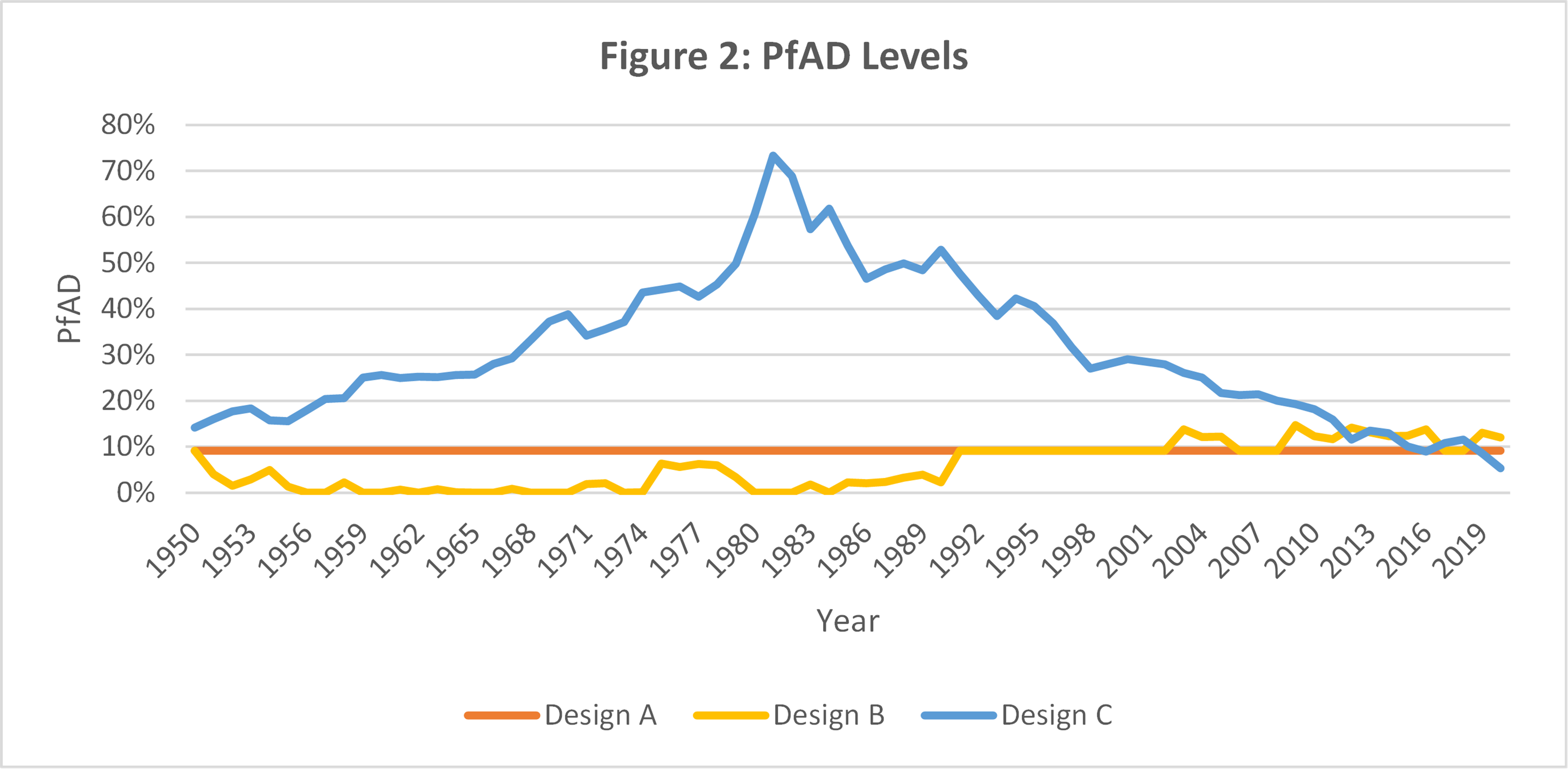

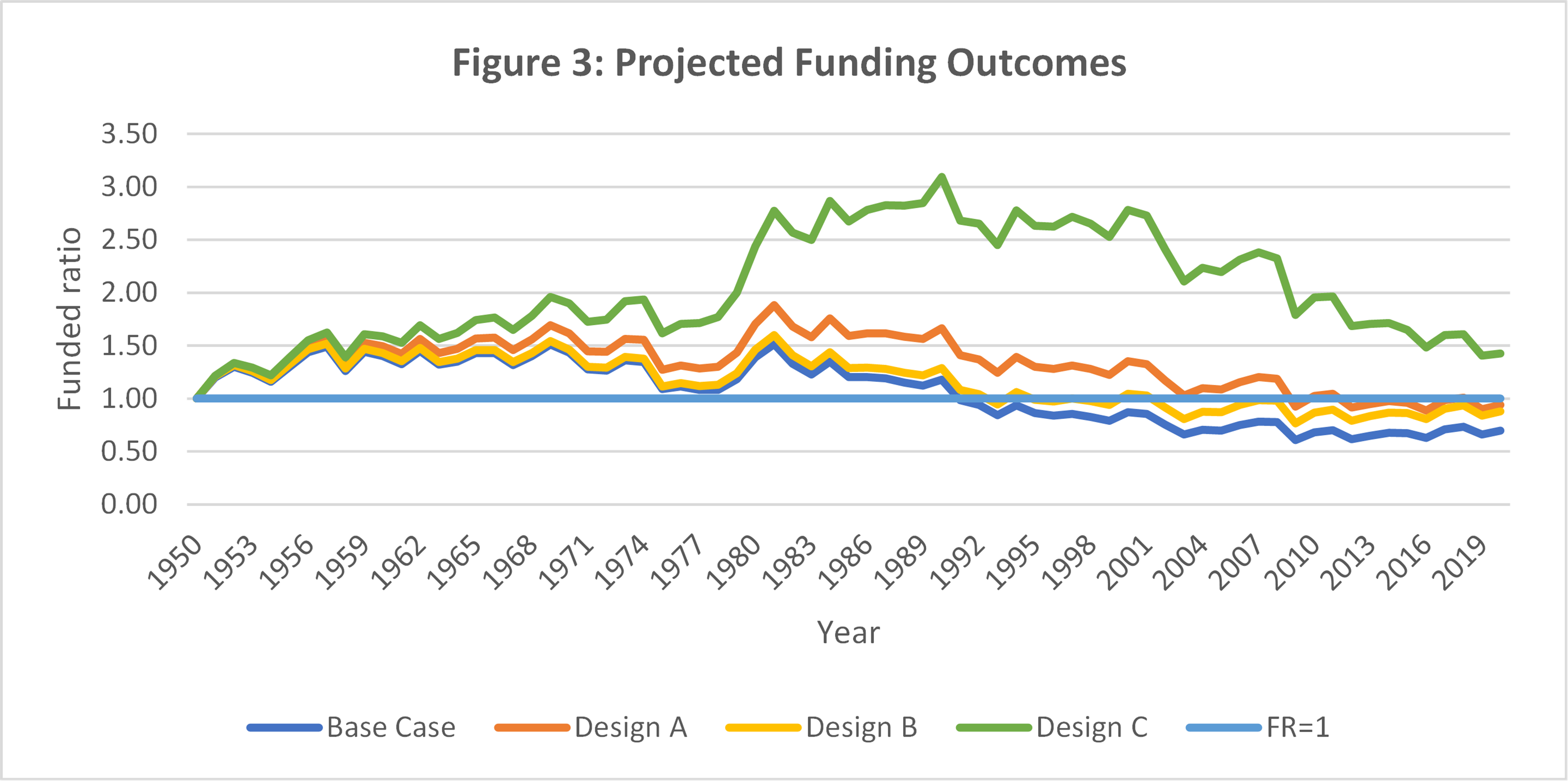

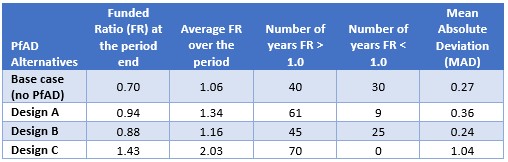

The average PfAD amounts applied over the period under the three design alternatives were determined to be 9.1%, 5.6%, and 31% respectively. The year-by-year PfADs and funded ratios over the 70-year period, as well as certain funded ratio statistics, are presented in the following graphs and table.

Table: Selected statistics on funded ratio

The mean absolute deviation (MAD) in the table is a measure that indicates the average distance between the observed funded ratio and the target funded ratio, which is set equal to 1.0.

Observations

All PfAD design alternatives show an increase in the funding level compared to the base case. However, the required PfAD under Design C is notably higher than the other two alternatives. This could potentially result in the plan becoming excessively overfunded, which undermines intergenerational equity.

Design B (dynamic PfAD) demonstrates a lower MAD compared to Design A (static PfAD). This suggests that plans with a PfAD under Design B are likely to follow a funding path that is closer to the target funded ratio than those under Design A. As a result, Design B is a preferred option for developing a long-term funding strategy for pension plans.

To verify our results, we conducted additional testing for three other time periods: 1950-1985 (35 years), 1967-2002 (35 years), and 1985-2020 (35 years). The findings from these tests are consistent with our original observations.

Implications for Plan Sponsors and Pension Fund Managers

The findings of this study have important implications for plan sponsors and pension fund managers. They suggest that a dynamic PfAD policy can help plan sponsors manage funded ratio risk more effectively, while also reducing the potential of excessive overfunding.

Under a dynamic PfAD policy, pension fund managers will need to monitor the plan's funded ratio more closely and adjust the PfAD accordingly. This will require a more proactive approach to risk management, as well as a more robust and sophisticated risk management framework.

Plan sponsors, on the other hand, will need to work closely with their pension fund managers to ensure that the plan's investment strategy and risk management framework are aligned with their long-term funding objectives and risk tolerance. They will also need to monitor the impact of changing PfAD requirements on the plan's funding position and contribution requirements, and make appropriate adjustments to their funding policies as necessary.

Finally, government policymakers will need to consider the implications of these findings for future pension funding reforms. The adoption of a dynamic PfAD policy may require changes to the regulatory framework governing pension plan funding, including the establishment of clear guidelines and standards for determining the PfAD and adjusting it over time.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. For one, the analysis is based on a hypothetical pension plan with a stationary membership profile and a 50/50 target asset mix, and may not be applicable to other types of pension plans with different investment strategies and demographic characteristics. Additionally, the analysis assumes that the PfAD is determined based on a fixed set of criteria and is adjusted at regular intervals, whereas in practice, the determination and adjustment of the PfAD may be more complex and depend on various factors, such as the plan's funding position, investment strategy, and demographic characteristics. Lastly, since the analysis relies on historical data, it assumes that future investment returns and bond yields will follow similar patterns, which may not be the case.

Future research could address some of these limitations by conducting a more comprehensive analysis of the impact of different PfAD designs on a broader range of pension plans with different investment strategies and demographic characteristics. This analysis could also consider the impact of different economic scenarios and assumptions about future investment returns and bond yields on the funding position of pension plans.

Conclusion

The adoption of a dynamic PfAD policy can help plan sponsors and pension fund managers manage funded ratio risk more effectively, while also reducing the potential of excessive overfunding. A dynamic PfAD policy requires a more proactive approach to risk management, as well as a more robust and sophisticated risk management framework. Plan sponsors and pension fund managers will need to work closely together to ensure that the plan's investment strategy and risk management framework are aligned with their long-term funding objectives and risk tolerance. Policymakers will need to consider the implications of these findings for future pension funding reforms and provide additional support to pension fund managers to help them manage the increased complexity associated with a dynamic PfAD policy.

Chun-Ming (George) Ma, FSA, FCIA

George Ma is a retired actuary with over 30 years of experience in retirement consulting and prudential pension regulation in Canada. Before his retirement in 2014, he was the Chief Actuary at the Financial Services Commission of Ontario where he provided advice to government policy makers, pension industry professionals and the general public on regulatory and actuarial matters related to registered pension plans in Ontario. Between 2012 and 2022, he was an Adjunct Professor at the University of Hong Kong responsible for teaching pension mathematics. He is a fellow of the Society of Actuaries and the Canadian Institute of Actuaries and holds a PhD degree in mathematics.

Dr. Ma is interested in seeking innovative solutions to address the demographic and financial challenges faced by public and private pension systems. He has written and spoken about topics on financial management of retirement plans.