Articles of Interest

Has a U.S. Exceptionalism Theme Left Global Portfolios Exposed to Concentration Risk?

U.S. exceptionalism can perhaps be thought of as a notion or belief that the United States is a fundamentally superior nation across many fronts, including but not limited to technological advances, military superiority, political influences and economic dominance. This ideology has shaped the direction and fueled the advance of the nation for well over 100 years. Specifically, as this theme relates to investing, U.S. exceptionalism has often played an important role in how investors, both U.S. and foreign, have viewed the relative attractiveness of the world’s biggest market – from high levels of confidence in the U.S. economy, depth of its financial markets, and the ability of U.S. companies to often outperform global competitors, all have been contributing factors.

The exceptionalism theme has gained steam in recent years, leading to a concentration of capital in U.S. assets, particularly equities, and more specifically technology stocks. This concentration has pushed the U.S. stock markets to historically high valuation levels, levels that, by past readings, point to the possibility of sub-par returns over the coming years. What has led to this heightened level of perceived exceptionalism? Several factors, including dominance of the U.S. in areas of technology, stronger economic growth relative to peers and a stock market structure supported by unequalled liquidity advantages.

Taking each in turn, America has a history of dominance in technological trends, from the personal computer (PC) in the early 1990s, the adoption of the Internet roughly a decade later, to the smart phone a further decade on. To this day, the U.S. remains the global leader in disruptive technologies, with companies such as Apple, Amazon, Google, Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla responsible for developing, growing and dominating their respective markets. This dominance has led to advantages across the technology landscape in the hiring of talent and the raising of capital. These companies, which grew to be known as “The Magnificent 7”, experienced exceptional growth in revenues and profits over recent years, with investors viewing them as must-own assets, crowding into their stocks and fueling valuation premiums relative to the overall market. According to investment bank, BNP Paribas, the so-called “Magnificent 7” technology companies have collectively grown their earnings by nearly 1,200% over the eight years ending in 2023, averaging 36% earnings growth per year. Over the same period, the share price advances of these companies more than met the prodigious growth delivered in earnings, and in doing so propelled this select group of growth stocks to eventually represent a near 35% of the broadly comprised S&P 500 Index – an historically high concentration level for such a small group of stocks.

Coming out of the Covid pandemic, the U.S. economy proved its resilience and dynamism once again, outpacing the slower growing economies such as those within Europe, Japan, United Kingdom and even China. Lower levels of unemployment, higher wage growth and more supportive demographics have provided support in contrast to other nations. Growth is a fuel for corporate profits, and corporate profits are a key driver of stock prices. An additional incentive for capital to favour America over the perceived stagnation of other developed markets during this time period.

Another important factor that has played a key role in fueling the exceptionalism theme within the U.S. markets relates to the size and structure of the market itself. Of the roughly $120 trillion in total stock market capitalization globally, the U.S. comprises about half of that, a stock market with a staggering $60 trillion value offering the depth and liquidity to attract capital from all corners of the globe. For comparison purposes, the European Union rings in at around $15 trillion, and Canada roughly $3 trillion. This superior position, coupled with the dominance of the underlying stock market indices over the past decade or so, has helped fuel tremendous growth in the ETF market. This growth has provided increasing opportunities for assets to move from active management into a variety of passive options, from the “plain vanilla” broad base market exposures to very niche and sector specific products like a Magnificent 7 ETF. The U.S. ETF market is one of the largest globally with assets under management exceeding $8 trillion, up from roughly $2 trillion a decade ago. This exceptional growth in assets has no doubt helped propel the U.S. stock market higher and contributed to the increased concentration we have witnessed within the key benchmark index, the S&P 500. Being a market capitalization weighted index, the more assets that come into products like an S&P 500 Index ETF, the more the stocks at the top of the heap benefit…wash, rinse, repeat. This can of course work in the opposite direction if assets begin to move out of such derivative-type products, with a high likelihood of adding weight to a falling market.

While the U.S. commands roughly 50% of the global market capitalization, its share of global GDP (gross domestic product) falls somewhere closer to 25%. This discrepancy is likely a result of the exceptionalism theme. To highlight this differential further, the MSCI All Country World Index, which is the gold standard benchmark for globally focused investment portfolios, has seen their allocation toward U.S. stocks climb to a record high of 67% of their global mix in recent months. Allocators who use an index such as the MSCI to determine their global equity mix may be at risk of being over exposed to the U.S. markets, especially if layered on top of separate allocations toward the U.S. If the MSCI World Index is used, which focuses on just the developed markets of the world, also a highly used index, the concentration is even higher, a near 73% U.S. allocation. This extraordinary weight allocated toward the U.S. appears out of line with the country’s economic stature and even its overall market capitalization. This discrepancy however wasn’t always present. For much of this century, until about 2017, the allocation averaged between 45-50%; and if we go back a little further to 1990, the U.S. and Japan were roughly equal in importance with each having roughly a 30% allocation. Interestingly, Japan’s weight in the Index actually fell from levels closer to 40% a few years prior.

Japan was experiencing its own bout of exceptionalism in the 1980s, a period of extreme asset inflation, speculative excess and rapid economic growth, which eventually collapsed in the early 1990s. During Japan’s peak heyday years of 1985-1989, the country’s leading benchmark stock market index, The Nikkei 225, tripled in value. The Index peaked at a level of 38,915…a mark not seen again until 2024. Today, Japan represents only 5% of the MSCI All Country World Index. An extraordinary tale of financial euphoria, driven by a theme of exceptionalism, that was followed by a very painful and lengthy reckoning.

Equating the U.S. today to Japan of the 1980s isn’t completely fair. The level of exuberance was off the charts in Japan. Asset prices, jet propelled by loose monetary policy, went through the roof. It was said that the land around the Imperial Palace in Tokyo hit the equivalent of the value of the entire state of California. The Japanese’s asset bubble ranks as perhaps the greatest on record and its deflating was painful for those over-exposed. While the U.S. market, as represented by the S&P 500 Index, is currently expensive by historical measures, its not into ridiculous territory; the reason for that is that the 493 stocks within the S&P 500 Index which are outside of the Magnificent 7, are as a group valued closer to long-term averages. Most of the market risk; however, lies with the smaller group of stocks, which have collectively driven the market higher in recent years and due to their dominance have come to represent “the market” given their near 36% weighting within the S&P 500 Index and approximate 23% of the MSCI World Index. This elevated concentration represents significant stock-specific risk to managed U.S. and Global portfolios.

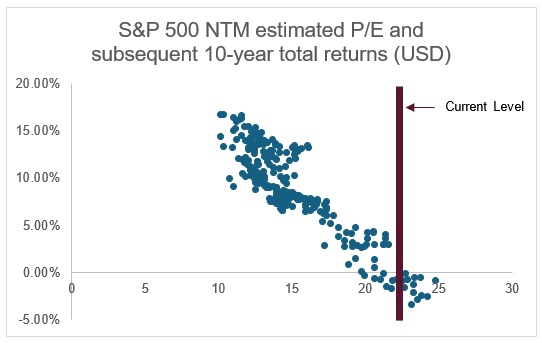

Valuation risk has been notable within the U.S. market of late, and specifically amongst these technology-related stocks. At their peak in 2024, this select group of stocks were valued at roughly 35x expected earnings, taking the valuation of the entire market higher along with it. The price paid matters in the world investing, and with market multiples in the U.S. at current levels, future returns begin to look paltry at best. The last time the U.S. stock market was valued at similar levels was at the height of the dot-com bubble at the turn of the Millenium. Similarly, a period in which a technology-driven mania (advent of the Internet) sent U.S. stocks to dizzying heights. The U.S. market peaked at roughly 25x expected earnings in early 2000. From that point of overevaluation, the S&P 500 Index delivered a total return (including dividends) of -0.95% over the ensuing decade – valuation risk exemplified.

The Price Paid Matters

Source: Sionna Investment Managers and FactSet. Data using NTM estimated P/E, monthly data from 07/31/1992 to 12/31/2024.

How much further can a U.S. exceptionalism theme take stock valuations? We are already into what is often considered by market historians and strategists as “danger territory”. Given the current dominance of the U.S. within MSCI World benchmarked portfolios, waiting for a cue from an index provider to reduce exposure may prove a costly and untimely approach. Developed markets of Europe, Japan and Canada have offered far better valuations in recent times; while these markets have under-performed the mighty U.S. in recent years, history shows that this hasn’t always the case. Its time for investors to think about re-balancing away from an over-exposed U.S. stock market, as history suggests the risks of not doing so could prove detrimental to plan returns over the coming years.

Stephen F. Jenkins, CFA, Co-CIO, Sionna Investment Managers

Stephen joined Sionna in 2019 and is the Co-Chief Investment Officer. He is the co-lead Portfolio Manager for Sionna high conviction strategy and the lead portfolio manager for the firm’s global value strategy and focused U.S. value strategy. Stephen has more than 30 years of experience in both domestic and global equity markets. He began his career in 1990 as an analyst at Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance Company and was most recently Senior Portfolio Manager and Senior Vice President at CI Harbour Funds. Stephen currently sits on The Niagara Community Foundation's Investment Committee. Stephen is a graduate of Wilfrid Laurier University, where he earned an Honours Bachelor of Business Administration degree and is a CFA® charterholder.