Articles of Interest

Doomed to Repeat It - What History Teaches Us About Risk Management

As we enter the second quarter of 2025, it seems that the uncertainty facing the market is only growing. Trade conflicts, war, political unpredictability, inflation fears, and stretched valuations present a combination of challenges that most market participants have not faced in their lifetimes. The recent sell off in the equity markets is a reminder that financial markets often price extreme price moves as though they are highly unlikely to occur. In fact, despite recent widening, at the time of writing – the 7th of April – credit spreads, (the compensation investors demand for taking default risk) remain near multi-decade tights.

The paradox of market behavior is that we simultaneously tell ourselves that shocks are extremely rare, and that today’s problems are worse than yesterday’s. Neither story is true.

Myth 1: Crises are Rare

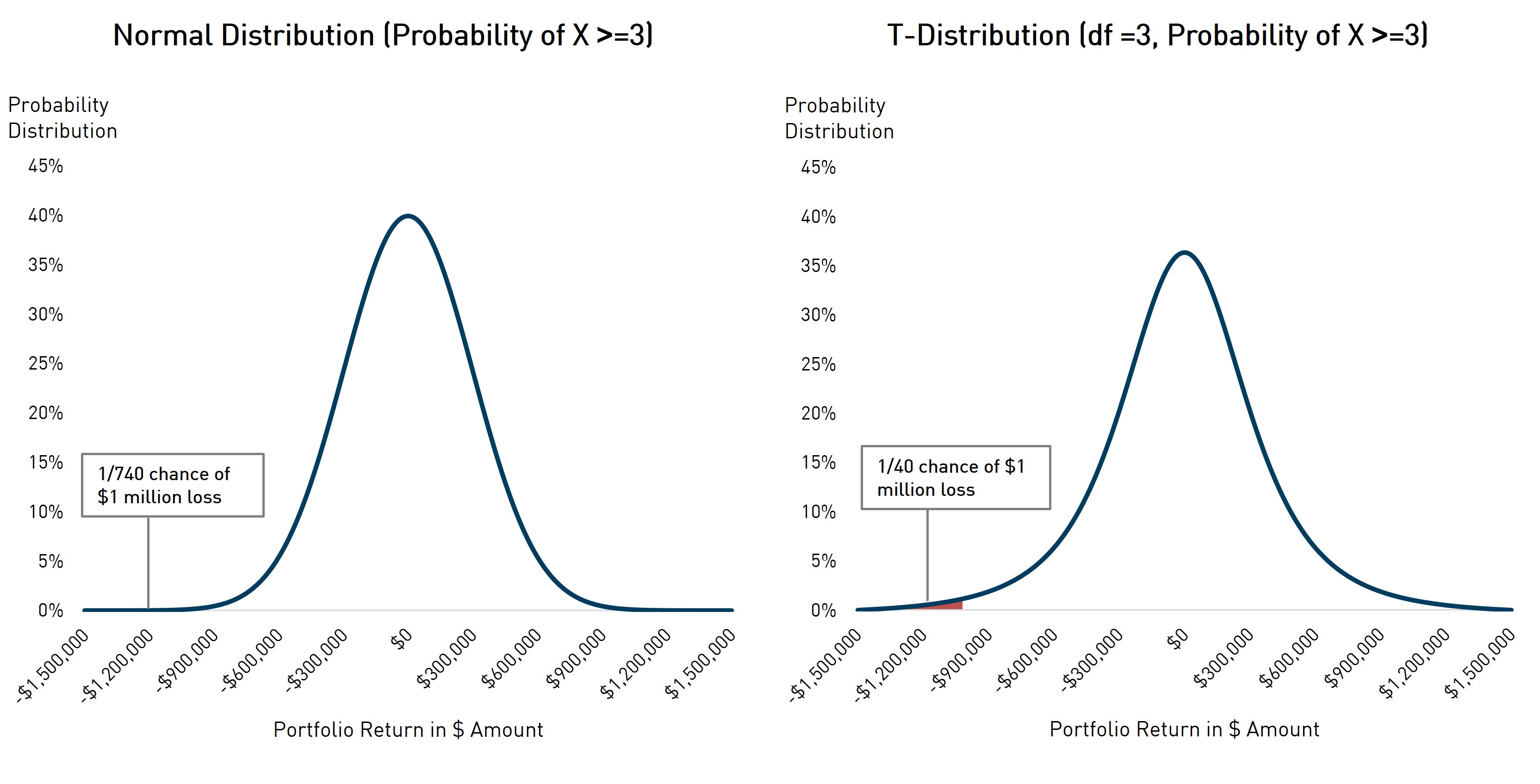

While investors consistently acknowledge the uncertainty under which they operate in general terms, they often fail to properly account for extreme outcomes. That is why most risk models try to incorporate “fat tails” in their distributions, ensuring that the relatively frequent occurrences of big price movements are mathematically accounted for.

In contrast, most people’s mental models consign very large price movement to the realm of inconsequential probabilities. Most people remember the normal distribution from school, which unfortunately and inadvertently reinforces this bias. For example, the S&P 500 lost 12% in its worst day following the onset of COVID in 2020. That was roughly a 10 standard deviation event. Using the normal distribution, the odds of that occurring are one in 131 sextillion (131 x 1023). That means the normal distribution would predict that a day like that would happen less than once in 180 billion lifetimes of the universe. Yet it happened. As did the 1987 crash, the dotcom bust of 1999-2001 and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Each of these recent events caught the market by surprise even though we know that pandemics, financial euphoria and banking crises are regular features of the economy. This combination of recency bias and a neglect of base rates of probability leads people to ignore the tails of the distribution repeatedly, even though simple math cautions otherwise.

Myth 2: Today’s Crises are Worse Than Yesterday’s

On the other side of the equation, today’s troubles always seem more complex and less tractable than yesterday’s. That is for three reasons:

- Yesterday’s problems have been solved already, so we know how the story ends.

- Humans are prone to nostalgia and declinism (for evidence we need look no further than the appeal of the promise to “Make America Great Again” to millions of voters in the United States, twice).

- Today’s world is uncertain, meaning that we cannot quantify the probability of any event or set of events occurring. History, by contrast, is known and therefore may be described as risky. For example, we know exactly how many times since 1927 the S&P 500 has sold off 20% or more but we cannot accurately estimate the probability that it will do so again this year.

When combined, the dueling narratives of (1) the extreme being less likely than experience has demonstrated and (2) today’s world being uniquely complex, is toxic to investors. It leads to confusion at best and paralysis at worst. So how to combat them?

The Art and Science of Risk Management

In Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Caroll wrote, “What is the use of a book, without pictures or conversations?” Similarly, what use is mathematical risk modeling if we cannot make it resonate? My team and I certainly use fat-tailed distributions in our mathematical risk modeling. It would be irresponsible to do otherwise. But the art of risk management lies in the way we communicate our analysis; how we tell stories. For deep evolutionary reasons, humans are wired to respond strongly to stories. This is why heuristics and mental shortcuts often win out over statistical reasoning in matters of public policy. The same is true in the world of investing. A well-told story is easy to process and remember, whereas statistics require effort to interpret.

The power of storytelling

To make the example vivid, imagine a risk manager approaching a portfolio manager carrying two charts, one with the normal distribution and the other with a fancier, more appropriate distribution (one that has fatter tails). She says to the PM, “While you may think the probability of losing a million dollars in a 3-standard deviation event is one-in-740, as the normal distribution implies, it is not. Rather, it is one-in-40 as my distribution chart clearly demonstrates.”

You can envision the look on his face. First of all, both one-in-740 and one-in-40 are likely small enough to be nearly indistinguishable to the PM. Second, the distributions are abstract rather than concrete. Finally, the math is purely hypothetical. The PM has not lost a million dollars, nor is he likely to. He can easily dismiss the risk manager's concerns and, in the absence of a willingness to force the position smaller, the risk manager has accomplished little.

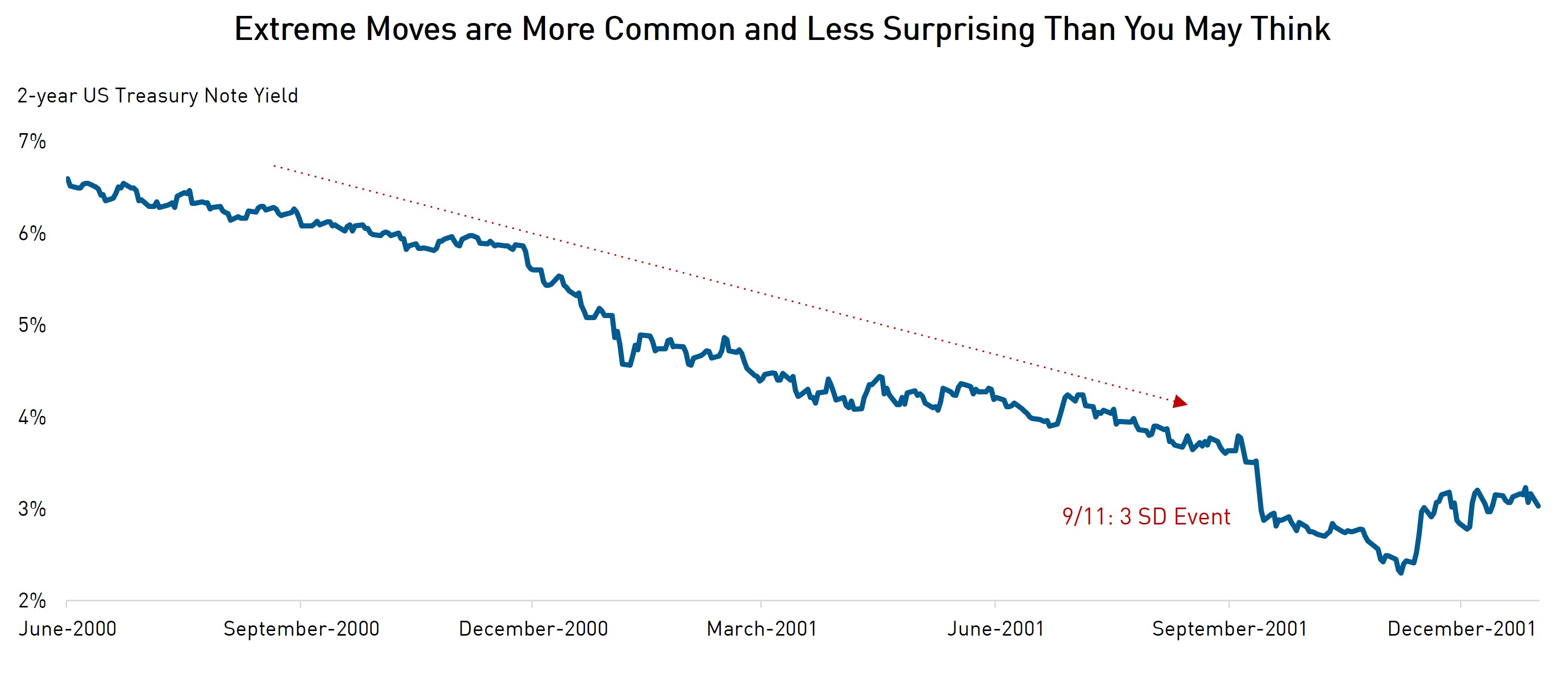

Now imagine she approaches with a different tactic. She pulls up her chair and tells the PM what she was doing on September 11, 2001. She describes what occurred and that it happened after the S&P had mired itself in a 25% bear market, the US Treasury two-year note had rallied over 300 basis points, and the Loonie had traded from $0.70 to $0.63. Then she shows him how his portfolio would have responded. He would not have lost a million dollars that day. He would have lost three million dollars. Nobody saw it coming, and that was after the huge moves that had preceded it.

Source: Bloomberg.

She has made an authentic connection, not an abstract point. Her argument is concrete, real. If the PM is old enough, he will certainly remember where he was that day.

There are, of course, limits to scenario analysis like this. Since no two crises are the same, it is obviously not a prediction of future results – you don’t want to fight the last war. Uncertainty seems worse than risk, which puts the risk manager and the PM in danger of overcorrecting. The PM may be too young to relate at all (in that case the risk manager should have chosen a better example). Nonetheless, she got his attention. Only once that has occurred can they address the details of today’s situation and forge their path accordingly.

Putting the story into today’s context

Once context is established, only then do we return to the models. Upon returning to them, however, the risk manager should carefully adjust her correlation matrix to suit the market environment as well as history. That crucial step can be the difference between fully understanding the risks in a portfolio and missing them entirely. A long duration, long credit portfolio would have performed one way in the 2018 trade war but entirely differently during the 2022 hiking cycle and differently again in the current trade battle.

That is why it may be wise to consider selecting some members of a high-status risk management department from among former senior members of risk-taking departments on the sell side. The object is to bring a critical eye to not only what distributions and correlation matrices we choose but also to the types of shock we may test for at any given time. In addition to testing the standard set of historical and statistical scenarios, a prudent risk manager should also test for what may lie around the corner. It is part of her job to always have an eye toward widening the set of possible outcomes in the minds of the PMs she works with. The wisdom that comes from having ‘lived it,’ combined with the analytical power of the risk models creates a powerful combination for constructing a risk framework.

The object is to bring experience to assessing the likelihood of a set of shocks that, while perhaps absent from history or not contemplated by off-the-shelf models, could portend unacceptable losses in the portfolios in question. By asking herself what may cause a given correlation to break down, a specific hedge to move in unexpected ways, or a counterparty to become adversarial, the risk manager is ensuring that the mental models and heuristics of the portfolio management staff have fat tails of their own.

Preparing for the Crises of Tomorrow

Today’s challenges are likely neither uniquely severe nor uniquely benign. They are part of the ongoing cycle of market evolution, where new risks emerge and new solutions follow. Investors who acknowledge uncertainty while preparing for a range of outcomes – both extreme and ordinary – will be best positioned to navigate the markets. The greatest risk is not uncertainty itself, but the failure to account for its full range of possibilities.

Alex Evis, Principal, Chief Risk Officer, RPIA

Alex Evis is the Chief Risk Officer and the Chair of the Risk Committee at RPIA. He also sits on the firm’s Investment and Executive Committees. Since joining RPIA in 2021, Alex has been instrumental in leading the firm's risk management team, creating and managing risk policies for all the firm’s offerings, and in guiding the firm's hedging strategies. Alex has over 20 years of experience in fixed income trading, business strategy, and risk management. Prior to joining RPIA, he spent 18 years at Goldman Sachs in New York, where he was a Managing Director since 2009. From 2015 to 2021, he led the Counterparty Risk Management and Market Transition teams globally. Alex holds a BSc and an MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.